The Earliest Days of the Electric Guitar

The Rickenbacker International Corporation (RIC) grew out of the first company founded for the sole purpose of creating and manufacturing fully electric musical instruments and amplifiers-the Los Angeles-based Electro String Instrument Corporation. Founded in 1931 by Adolph Rickenbacker and George D. Beauchamp, this pioneering firm produced “Rickenbacker Electro Instruments”, the first modern electric guitars. RIC’s history now spans 93 years in business on the leading edge of music trends that have changed popular culture forever. Played by Hawaiian musicians of the 1930s to jazz bassists of the 1990s, by the Beatles and Byrds to the most-current rock groups on MTV, the ringing sound of Rickenbacker instruments has helped define music as we know it. Never resting on its laurels, RIC continues to ignite and propel the electric guitar’s transformation of music by providing today’s musicians with the finest instruments available.

It all began in 1920s Los Angeles, a city fast becoming the entertainment capital of the world. Like many of his contemporaries, steel player George Beauchamp (pronounced Beechum) sought a louder, improved guitar. Several inventors had already tried to build louder stringed instruments by adding megaphone-like amplifying horns to them. Beauchamp saw one of these and went looking for someone to build him one, too. His search led to John Dopyera, a violin repairman with a shop fairly close to Beauchamp’s L.A. home.

Dopyera and his brother Rudy’s first attempt for George sat on a stand; a Victrola horn attached to the bottom and pointed towards the audience. It was a failure, so the Dopyeras then started experiments with thin, cone-like aluminum resonators attached to a guitar bridge and placed inside a metal body. A successful prototype (soon dubbed “the tri-cone”) used three of these resonators. Beauchamp, so pleased with the results, suggested forming a manufacturing company with the Dopyeras, who had already started making more guitars in their shop. Setting out to find investors, he took the tri-cone prototype and the Sol Hoopii Trio (a world-famous Hawaiian group) to a lavish party held by his millionaire cousin-in-law, Ted Kleinmeyer. He was so excited about the guitar and the prospects for a new company that he gave Beauchamp a check for $12,000 that night.

Substantial production of the metal-body guitars began almost immediately. Beauchamp, acting as general manager, hired some of the most experienced and competent craftsmen available, including several members of his own family and the Dopyeras. He purchased equipment and located the new factory near Adolph Rickenbacker’s tool and die shop. Rickenbacker (known to his friends as Rick) was a highly skilled production engineer with experience in a wide variety of manufacturing techniques. Swiss-born, he was also a relative of WWI flying ace Eddie Rickenbacker. Well equipped to manufacture metal bodies for the Nationals, Adolph owned one of the largest deep-drawing presses on the West Coast and soon carried the title of engineer in the National Company.

Unfortunately, the seeds for an internal dispute within National were planted in the very beginning. By late 1928 the Dopyeras became very disgruntled with the management of company and resources. John Dopyera, who rightfully considered himself an inventor, ironically thought that Beauchamp wasted time experimenting with new ideas. Dopyera and Beauchamp lived in two different worlds and apparently were at odds on every level of personal, business and social interaction. That they could not work together successfully was a foregone conclusion. Another problem was Ted Kleinmeyer, who had inherited a million dollars at 21 and was trying to spend it all before turning 30 (when he would inherit another million). A Roaring ’20s party animal, successful losing money faster than he could make it, he started hounding Beauchamp for cash advances from National’s till. George’s fault was that he could not turn people down, especially his friends and the company’s president.

John Dopyera quit and formed the Dobro Corporation, but maintained National stock. The Dopyera brothers would eventually win more in a court settlement. Then Ted Kleinmeyer, nearly broke (and a few years away from the rest of his inheritance), sold his controlling interest in the concern to another Dopyera, brother Louis. In a shakeup that followed, Beauchamp and several other employees were fired. Now George needed a new project and a new company, fast.

Along with others of his day, he had thought about the possibility of an electric guitar for several years and, though not schooled in electronics, had started experimenting as early as 1925 with PA systems and microphones. Early on he made a single-string test guitar out of a 2×4 board and a pickup from a Brunswick electric phonograph. This experiment shaped his thinking and put him on the right path. After leaving National, he began his home experiments in earnest and attended night-school classes in electronics.

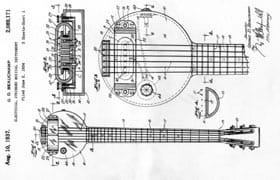

By 1930 many people familiar with electricity knew that a metal moving through a magnetic field caused a disturbance that in turn could be translated into an electric current by a nearby coil of wire. Electrical generators and phonograph pickups utilized different applications of this principle. The problem building a guitar pickup was creating a practical way of translating the strings’ vibration directly into a current. After many months of trial and error, George developed a pickup that consisted of two horseshoe magnets. The strings passed through these and over a coil, which had six pole pieces concentrating the magnetic field under each string. (Conducting work on his dining room table, he used the motor out of the family washing machine to wind the coil. Paul Barth, who helped Beauchamp, said that they eventually used a sewing machine motor.)

When the pickup seemed to be doing its job, Beauchamp called on Harry Watson, a skilled craftsman who had been National’s factory superintendent, to make a wooden neck and body for it. In several hours, carving with small hand tools, a rasp, and a file, the first fully electric guitar took form. It was nicknamed the “Frying Pan,” for obvious reasons. Anxious to manufacture it, Beauchamp enlisted his friend Adolph Rickenbacker. With Adolph’s help, know-how, ideas, and capital were abundant. The first name of the company was Ro-Pat-In Corporation but was soon changed to Electro String. Adolph became president and George secretary-treasurer. They called the instruments Rickenbackers because it was a famous name (thanks to cousin Eddie) and easier than Beauchamp to pronounce. Paul Barth and Billy Lane, who helped with an early preamplifier design, both had small financial interests in the company as production began in a small rented shop at 6071 S. Western Ave., next to Rickenbacker’s tool and die plant. (Rick’s other company still made metal parts for National and Dobro guitars and Bakelite plastic products such as Klee-B-Tween toothbrushes, fountain pens, and candle holders.)

Electro String had several obstacles. Timing could not have been worse–1931 heralded the lowest depths of the Great Depression and few people had money to spend on guitars. Musicians resisted at first; they had no experience with electrics and only the most farsighted saw their potential. The Patent Office did not know if the Frying Pan was an electrical device or a musical instrument. What’s more, no patent category included both. Many competing companies rushed to get an electric guitar onto the market, too. By 1935 it seemed futile to maintain a legal battle against all of these potential patent infringements.

Hawaiian guitars (lap steels) would be the best known and most accepted 1930s Rickenbackers. Early literature illustrates both 6- and 7-string versions of the Frying Pan. Both had the same cast aluminum construction, compared with the prototype’s wood. Over the years (this guitar would be available into the 1950s) two scale lengths would be offered: 22 1/2 inch and 25 inch. Workers stuffed the bodies and necks with newspapers, which today can provide a clue as to the guitar’s date of manufacture. Soon after the Frying Pan, several additional steel models were offered, the most popular being the hard-plastic Bakelite Model B, later named Model BD. The earliest examples had a volume control and five decorative chrome cover plates on top. By the late 1930s they had both tone and volume controls and white-enameled metal cover plates. In the 1970s, David Lindley used a Bakelite steel on many recordings with Jackson Browne, proving the integrity of the original design in a modern context. Many players consider these lap steels the finest ever produced.

Electro String’s first Spanish (standard) guitar had a flattop hollow body with small F-holes and a slotted-peghead. A bound neck joined at the 14th fret. By the mid-1930s, the concert-sized Ken Roberts Model (named after one of Beauchamp’s guitar-playing friends) came out. It had a bound neck that joined the body at the 17th fret, a shaded 2-tone brown top with F-holes, and a Kauffman vibrato tailpiece. In the 1930s and 1940s there were at least two electric arch top models. The SP had a maple body, shaded spruce top, bound rosewood neck with large position markers, and a built-in horseshoe pickup. The Model S-59 sported a blonde finish and a narrow, detachable horseshoe pickup. This so-called “Rickenbacker Electro peerless adjustable pickup unit” was also available as a separate accessory and would attach to most F-hole style arch tops.

Despite the popularity of arch tops, the 1935 Bakelite Model B Spanish guitar made the most history for Rickenbacker. Though not entirely solid (it had thick plastic walls and a detachable Spanish neck), it achieved the desired result-virtual elimination of the acoustic feedback that plagued big-box electrics of the day. It set the stage for all solid body guitars to follow, even though it was difficult to play sitting down on the bandstand. (A Bakelite Spanish the size most guitarists were accustomed to would have been as heavy, literally, as a sack of bowling balls.) A variation of the Bakelite Spanish invented by Doc Kauffman (who would later become Leo Fender’s first partner) was the Vibrola Spanish Guitar, an ungainly thing equipped with a motorized vibrato tailpiece. So heavy, it required a stand to hold it up.

From the very beginning Electro String developed and sold amplifiers. After all, the instruments worked only in conjunction with them. The first production-model amp was designed and built by a Mr. Van Nest at his L.A. radio shop. Shortly thereafter, Beauchamp and Rickenbacker hired design engineer Ralph Robertson to work on amplifiers. He developed the new circuitry for a line that by 1941 included at least four models. The speaker in the Professional Model was designed by James B. Lansing. Early Rickenbacker amps influenced, among others, Leo Fender who by the early 1940s repaired them at his radio shop in nearby Fullerton, California.

How did Rickenbacker guitars shape the 1930s music industry? Beauchamp had many friends and contacts in the entertainment community and as a result many stars used his instruments. Sol Hoopii and Dick McIntyre, to name just two popular Hawaiian steel guitarists, played Rickenbackers on countless influential recordings. Perry Botkin, who did many recording sessions with Bing Crosby and other Hollywood stars, used one of the few Vibrola Spanish Models. Les Paul owned a Rickenbacker. Electro String even made Harpo Marx an electric harp. A family of Rickenbacker Electro String Instruments was born, all using some variation of the horseshoe-magnet pickup. Besides guitars and mandolins, the company invented fully electric bass viols, violins, cellos and violas. An electric piano prototype sat in the firm’s front office for years. Most of these instruments totally disregarded traditional styling. Rickenbacker realized that a fully electric instrument did not have to retain the appearance of its acoustical counterpart. This conceptual jump-the first of several Rickenbacker revolutions-liberated the thinking of designers to come.

By 1940, after fifteen years in the fast lane, Beauchamp became frustrated and disenchanted with the instrument business, partly due to his deteriorating health. His second passion, fishing and designing fishing lures, captured his attention. He patented one that he sought to manufacture; to raise the necessary capital he sold his shares in Electro String to Harold Kinney, Rickenbacker’s bookkeeper. Soon after this, Beauchamp went deep sea fishing and had a fatal heart attack. His funeral procession was over two miles long. A true pioneer of electric instruments, he unfortunately did not live to see the electric guitar reach its full potential.

Adolph Rickenbacker had maintained other interests throughout Electro String’s short history; he never had as much faith in the guitar business as his partners. Nevertheless, he continued instrument making until 1953 when he sold the company to F.C. Hall, a leading figure in the post-WWII Southern California music business. That sale marked the end of one era and the beginning of another, the dawn of modern Rickenbacker guitars.

The Modern Era of the Electric Guitar

Francis C. Hall was born in Iowa in 1909 and moved to Southern California in 1919. His father owned a small store in Santa Ana, and F.C. went to work at an early age. As a high school student, he became interested in radios and electronics. Besides the obligatory homemade radio enterprising kids of the 1920s made for themselves, young F.C. started a part-time business recharging batteries, making home pickups and deliveries. By the time he had reached 18, he was manufacturing batteries at home for sale. The battery business evolved into a prosperous electronics-parts distribution company called the Radio and Television Equipment Company (R.T.E.C. or Radio-Tel). Hall’s solid background in electronics and public address systems, which he installed in many Orange County churches, schools, and meeting rooms, made his transition into the music industry almost a natural step.

Shortly after WWII, Hall started to distribute steel guitar and amplifier sets made in Fullerton by Leo Fender. In 1946, he became Fender’s exclusive distributor and set out to build a national distribution network. Hall played a key role in Fender’s early success by providing financial backing and parts at a time when electric guitar manufacturing seemed like a high risk venture to most businessmen. F.C. was one of the first people to recognize the bright business possibilities of amplified music, but gradually grew unhappy with his situation selling Fenders. Opportunity knocked again when Adolph Rickenbacker and other shareholders in Electro String sold their interests to him. John Hall says that his father wanted to pioneer the in-house sales organization where closer ties to the decisions made at the manufacturing level would better serve the customer’s needs. The purchase of Electro String by Hall and the distribution of its guitars by Radio-Tel thus set in motion the modernization of the Rickenbacker guitar line.

The early 1950s marked a period of major change in the guitar marketplace-the popularity and sales of steels waned as the popularity of regular guitars exploded. The advent of rock music in the mid-1950s was the coup de grace for non-pedal steel guitar-the electric Spanish guitar had proven itself more versatile and adaptable to the new musical styles. In other words, by the time Hall purchased Electro String, the trend was away from the company’s fine lap steels. To update the Rickenbacker line, he introduced the Combo 600 and 800 guitars, designed for the most part by factory manager Paul Barth. Each differed only in its electronics-the 800’s horseshoe pickup had two coils, the unpatented “Rickenbacker Multiple-Unit.” When used in combination, these coils were humbucking; when used separately, one coil accentuated treble and one bass.

In 1956, Rickenbacker celebrated its 25th anniversary with the introduction of the student model Combo 400 guitar, with what collectors call the tulip or butterfly-style body. Moreover, the firm soon added a solid body electric bass. Both instruments had a novel construction feature: their necks extended from the patent head to the base of the body. Today this is known as neck-through-body construction, with the sides of the guitar body bolted and/or glued into place. Rickenbacker was first to mass produce instruments like this, and the design would soon became a well-known trademark.

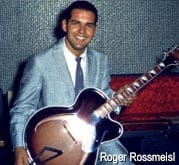

Perhaps the best known 1950s Rickenbackers were the hollow body 6-string Capri models, introduced in 1958. Designed for the most part by Roger Rossmeisl, there were three categories, each distinguished by a different body style. The first group had 2-inch-thick double-cutaway bodies, while the second group had 3 1/2-inch thick single-cutaway bodies. The third grouping was a catch-all category for instruments with even deeper bodies, including pure acoustics. All Capri styles came with or without Vibrato and with either two or three pickups. Customers chose either deluxe-style fingerboard inlays and bindings or standard inlays and no bindings. Capris had slim and narrow “fast action” necks, which appealed to many. Standard colors in 1958 included Hi Lustre Blonde (a natural maple finish) and Autumnglo (a 2-tone brown sunburst). Fireglo (the pink to red sunburst we now know so well) was added in 1959. Standard finishes for Rickenbacker solid bodies included Cloverfield blue-green, natural maple, gold-tinged Montezuma Brown, and Black Diamond. Virtually any color was available on any model by special order, and the factory made them. In the late 1960s the standard colors would include Azureglo-blue and Burgundyglo.

In the early 1960s Rickenbacker history became forever wedded to one of the biggest music upheavals of the 20th century: the invasion of the mop-top Beatles from Liverpool, England. The Beatles used several Rickenbacker models in the early years. Before the group broke up, John Lennon would own at least four. This love affair began in Hamburg, Germany in 1960 when he bought a natural-blonde Model 325 with a Kauffman vibrato. Lennon played the original (which was eventually refinished black but still easily identified by its gold-backed lucite pickguard) on all Beatle recordings and in all concerts until early 1964. (Listen for it especially on the rhythm track of the group’s “All My Loving.”) Rickenbacker provided Lennon with an updated 325 in early 1964–also painted black, it featured a solid top, Ac’cent Vibrato, and white pickguards. Lennon’s third Rickenbacker conformed closely to the features of the English distributor’s Model 1996. (In the 1960s Rose, Morris, Ltd., carried five Rickenbacker models in England. Generally, they had F-holes instead of cat’s eye slashes or solid tops. Ads in England called the Model 1996 the “Beatlebacker.”) Lennon’s fourth Model 325 was a one-of-a-kind 12-string version.

Paul McCartney used a Hofner bass in the early years of Beatlemania but soon had a Fireglo twin-pickup Rick bass, an early Model 4001S with dot inlays and no bindings. Its features closely resembled those of the Rose, Morris Model 1999 later played and made even more famous by Chris Squire of Yes. These solid body basses-which seemed so modern in the 1960s-used horseshoe pickups in the bridge position, thus proving the validity of Beauchamp’s original 1930s design. Good ideas are timeless.

While Paul’s Rick bass surged like an undertow, George Harrison’s double-bound 360/12 (the second one made by the company) defined a new tone at the other end of the audio spectrum. Its ringing sound embellished “You Can’t Do That,” “Eight Days a Week,” and “A Hard Day’s Night,” to name just three 12-string cuts from the 1964-65 period. Thus the Beatles created unprecedented, international interest in Rickenbackers, which many fans actually believed came from Britain.

Soon Rickenbackers created the sound and image of bands on both sides of the Atlantic. Jim (later Roger) McGuinn-who bought a Rickenbacker 360/12 after seeing the movie “A Hard Day’s Night”-literally made the bell-like quality of its tone the foundation of the Byrds’ early style. His later 3-pickup 370/12 featured custom wiring, but was still for the most part an off-the-rack instrument. The Who’s Peter Townshend, Creedence Clearwater Revival’s John Fogerty, Steppenwolf’s John Kay, and many other well-known 1960s guitarists became faithful Rickenbacker users. What had been a six-week waiting period from the factory for some models became a six-month (or longer) waiting period in the mid 1960s.

This rapid growth in demand led to changes in the company. Before 1964 all Rickenbacker guitars had been made at the original Electro String factory in Los Angeles. That year Hall moved it over a six month period to Santa Ana, in nearby Orange County. Despite the disruption in production during the transition, the new factory had increased production capacity. During this same period, the distributor Radio-Tele changed names to Rickenbacker, Inc., thus adopting a moniker people had used all along anyway. The company also added several novel guitars to its line.

The so-called convertibles came equipped with a lever that changed a 12-string neck into a 6-string neck. The Model 331- commonly called the “Light Show Guitar” because of its frequency-modulated internally-lit body-reflected the psychedelic 1960s in both sound and substance. The flashing began when the player hit the strings: yellow for treble notes, red for mid-range, and blue for bass. (Rickenbacker also produced a kaleidoscopic light projector called the Phantasmagorian.) Other oddities included the Bantar ( 5-string banjo meets electric guitar) and Eddie Peabody’s Banjoline (a 6-string with Ac’cent Vibrato that tuned like a 4-string tenor guitar). Rickenbacker introduced the hollow body 4-string 4005 and 6-string 4005-6 basses in the late 1960s. Several custom-ordered 8-string basses were also produced.

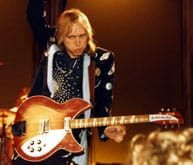

In the 1970s, Rickenbacker added guitars with detachable necks and redesigned single- and double-coil pickups. A patented feature on some new models, and an option on others, was slanted frets, which better matched the angle of the player’s hand. Two double-neck instruments became standard items: the model 4080 bass/guitar and the model 362/12 6/12-string. Rickenbacker basses dominated production during the early years of the decade-in many circles, a Rick bass was the only one to own. Then bands such as Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers and R.E.M. hit like their 1960s forerunners, using Rickenbacker 6- and 12-strings. As the saying goes, fashions go in and out of style. Style is always in fashion.

Today the manufacturing and distribution of Rickenbacker guitars and basses is combined into RIC, the name used since F.C. Hall retired in September 1984 and John Hall, along with his first wife Cindalee, became the sole owners of the company. RIC retains the spirit of first-class pre-1965 electric guitar manufacturing and craftsmanship. In addition to newly designed guitars and basses, the company offers faithful reissues of the classics played by the Beatles and other famous artists. RIC has offered highly successful, limited-edition signature models endorsed by such diverse players as Roger McGuinn, Pete Townshend, Tom Petty, Carl Wilson, and John Kay. Improvements in construction and quality control have carried Rickenbackers into the modern era, one that respects the company’s early history and at the same time sets out to write new chapters. Groups like Oasis, Pearl Jam, Radiohead, U2, and other of today’s top acts include Rickenbacker guitars in their musical arsenal.

A DJ once asked George Harrison if he liked a guitar he doodled on during a radio interview. Harrison is said to have quickly replied, “Of course, it’s a Rickenbacker!” Asked the same question 65 years after the invention of modern electrics, thousands of satisfied guitar players would say exactly the same thing.